The clinic is now being run by Thomas’s psychotherapist daughter Martha, and counts among its employees a local girl named Lena Fontana, whom Anton had paid for sex in 1927.

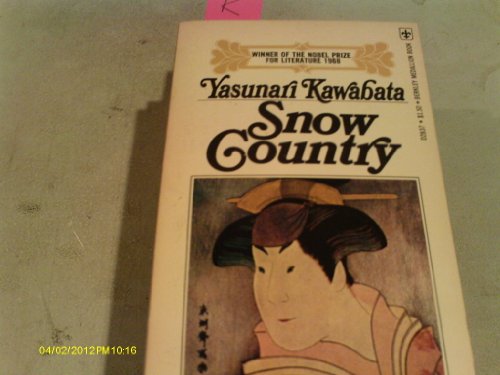

In 1934, an editor commissions him to report on the Schloss Seeblick, the psychiatric clinic outside Vienna which Drs Jacques Rebière and Thomas Midwinter established in the first book of Faulks’s “Austrian trilogy”, Human Traces (2005). When we meet him again in 1927, a grieving Anton has returned to Vienna and re-established himself as a writer of some note. Born in Styria in 1887, Anton moves to Vienna in 1906 to study philosophy, then works as a foreign affairs reporter until the outbreak of the First World War, at which point his French girlfriend Delphine Fourmentier (elder sister of Birdsong (1993)’s Isabelle) disappears and he enters the army in despair. In his new novel, Snow Country, Sebastian Faulks attempts something like a combination of all three of these methods, employing a third-person narrative voice that is closely focalised through the perspective of its male protagonist, Anton Heideck, with occasional departures to those of other characters.

In some historical novels, the problem never arises in the first place if the protagonist is principal secretary to King Henry VIII, the Reformation is bound to come up. Some authors supply an omniscient third-person narrator to plug possible gaps in historical knowledge, as in Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928), where Orlando sends a letter to “Mr Nicholas Greene of Clifford’s Inn” and helpful parentheses explain that “(Nick Greene was a very famous writer at that time).” Others have first-person narrators do the same job as they reflect retrospectively upon their own lives from a future vantage point, such as Tom Crick in Graham Swift’s Waterland (1983), who must note the “precise” date (“July, 1943”) during which the novel’s events took place in order for him to make emotional sense of them 40 years later.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)